‘Montes’ at Bolivar Hall

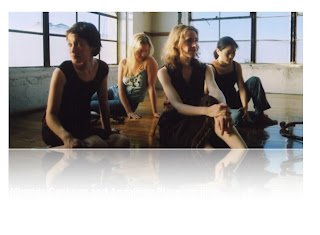

Jane Gordon, Adrian Charlesworth, Sara Jones and Jennifer Morsches. In the first image, I am acknowledging the Montes family who are in the audience. Photos by Richard Strike.

UK Première of String Quartet No 1 ‘Montes’

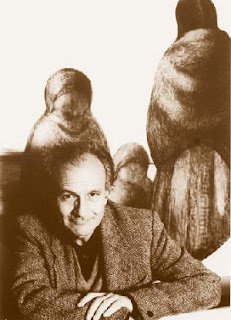

This was an intense experience. The music’s dedicatee, Fernando Montes, presided over the proceedings as if he were still here. His family did most of the organisational work making the event possible, whereas my music and, to a larger extent, Verónica Souto’s film The Spirit of the Andes, brought Montes’s work alive in front of an audience that was made up of Montes’s friends and admirers.

The string quartet experience was very different from the Philadelphia story. First of all, the London-based players were not a pre-existing string quartet, but came together especially for the occasion. This in itself was a considerable organisational challenge which started from the recruitment of the players. At the early stages of planning, if the project was deemed possible at all it had been because a string quartet of young, enthusiastic, new-music loving players, mainly Venezuelans, was deemed to be available to Bolivar Hall. When I made the necessary contact to ascertain the existence, youth and enthusiasm of the players I found that their existence and youth were a distinct possibility, but their enthusiasm was conspicuous by its absence. By this time the project preparations had taken off: the plan was to mark the first anniversary of Montes’s death at Bolivar Hall on 17 January, with a projection of Souto’s film and a performance of my quartet. Many people were working on that assumption. There was no turning back.

At this point enter Jennifer Morsches. She was remembered by the Montes family as a recent, but devoted friend of Fernando’s, and she was remembered by me as the excellent cellist who worked with Florilegium and whom I had seen, much to my surprise, playing romantic and twentieth-century music with Elizabeth Schwimmer in Cochabamba, Bolivia. On being approached about this project she showed unequivocal enthusiasm, and soon she was to prove true to her word. She took on the recruitment of the other players and the planning of the rehearsals, including the offer of her own house for them. When recruitment proved harder than expected her commitment was unwavering. She did not falter even when, two days before the first rehearsal and five days before the concert, her colleague Rodolfo Richter, appointed first violin, announced that he was pulling out because of a severe eye infection that required immediate surgery. Saturday 12 and Sunday 13 were spent in a flurry of phone calls between Jennifer, me and possible Richter replacements. The quartet seemed doomed to cancellation, but the thought of doing that to the Montes family was hard to stomach. Somehow Jennifer’s perseverance worked its magic, and by Sunday evening a replacement was in place in the form of Jane Gordon, violinist of the Rautio Trio.

I stayed out of the players’ way the day of the first rehearsal, Monday 14 January, and took the train down to London on the Tuesday. I found the players immersed in their discovery of the piece and of each other, riding on the crest of a very steep learning curve. The piece was new to them, so was the style, and so were they to each other. They were not exactly gliding over, but they were not sinking either. Good spirits saved them, and Jane Gordon saved them by taking the reins and leading with a firm hand. By the end of Tuesday the piece was far from ready, but the spirits far from broken.

On Wednesday, the day before the concert, there was to be no rehearsal because of another concert involving our superb cellist, by the early music group Florilegium. I knew this splendid ensemble since our Bolivian venture in 2005, so I took the opportunity to go and hear them. It was a lunchtime concert, in the bowels of Imperial College. The difficulties of finding this secret location even well after reaching the Imperial campus meant that I got there only for the second piece. I was taken aback by the sight of their virtuoso director, Ashley Solomon, playing Mozart with his foot in an elaborate contraption that appeared designed to keep his toes together. But more than that, I was taken aback by the sight of the violinist, Rodolfo Richter, playing with great aplomb and reading with seemingly unbloodied eyes from a music stand like everybody else, displaying an ocular resilience I had not thought him capable of in his current state. If anybody ever doubted that Mozart’s music can be miraculous, here was the proof. It heals the soul, it heals the eyes. The concert was truly enlightening. And Jennifer was the magnificent player I had always known her to be.

On Thursday 17 January, a year to the day since the death of Fernando Montes, a documentary about him and a string quartet about him received their British premières at London’s Bolivar Hall. Tickets had sold out weeks in advance. The Chairman of the Anglo-Bolivian Society, David Minter, gave a fitting tribute to the artist in his introductory address. Then I introduced the piece outlining each movement’s connection with a Montes painting. Vince Harris helped with the projection of the relevant paintings. Then my four friends played the string quartet, with an assurance that belied the short preparation time and a commitment that did not fail to stir and move. Then Verónica Souto introduced her film, and then the programme closed with the film itself.

It was a memorable occasion in many respects. Clearly Fernando Montes was foremost in the minds and hearts of all present. Several people had travelled a long way, some from abroad, for the occasion. It was an act of group catharsis, where the music and the film provided the ritual’s structure. I found it all deeply moving.